The Camel Man

- Written by Barry Ferrier

- font size

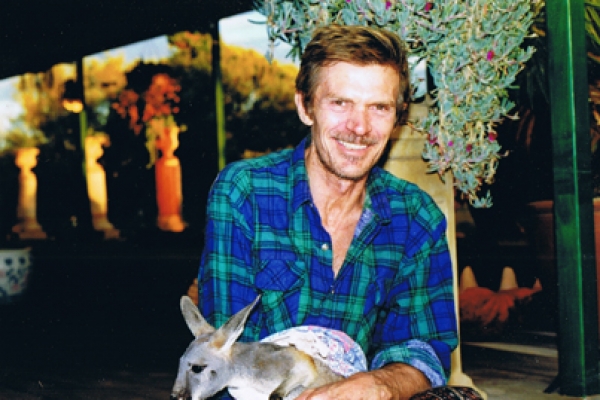

Memories of Rodney Gooch.

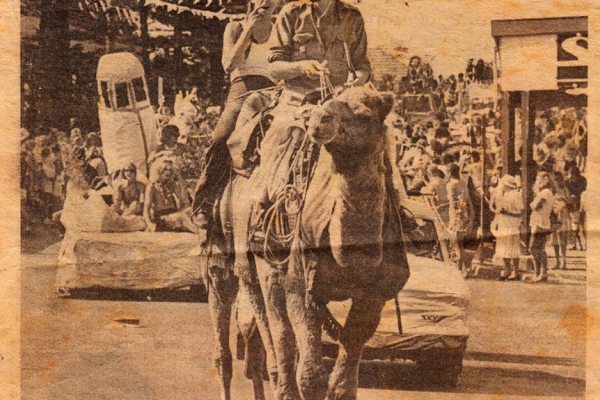

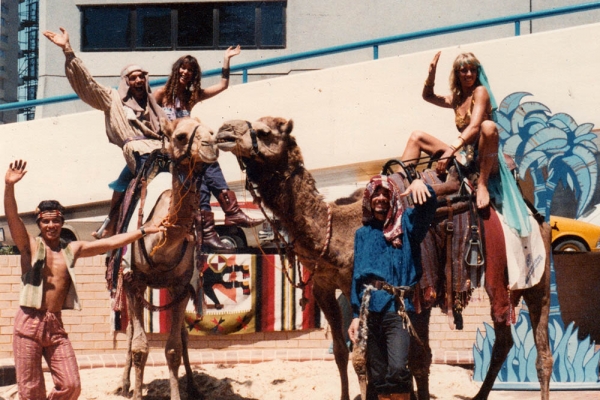

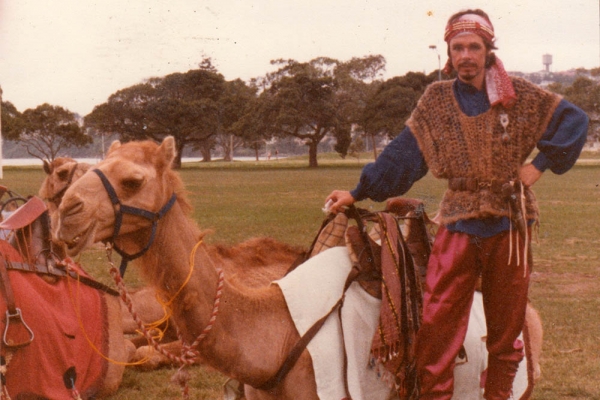

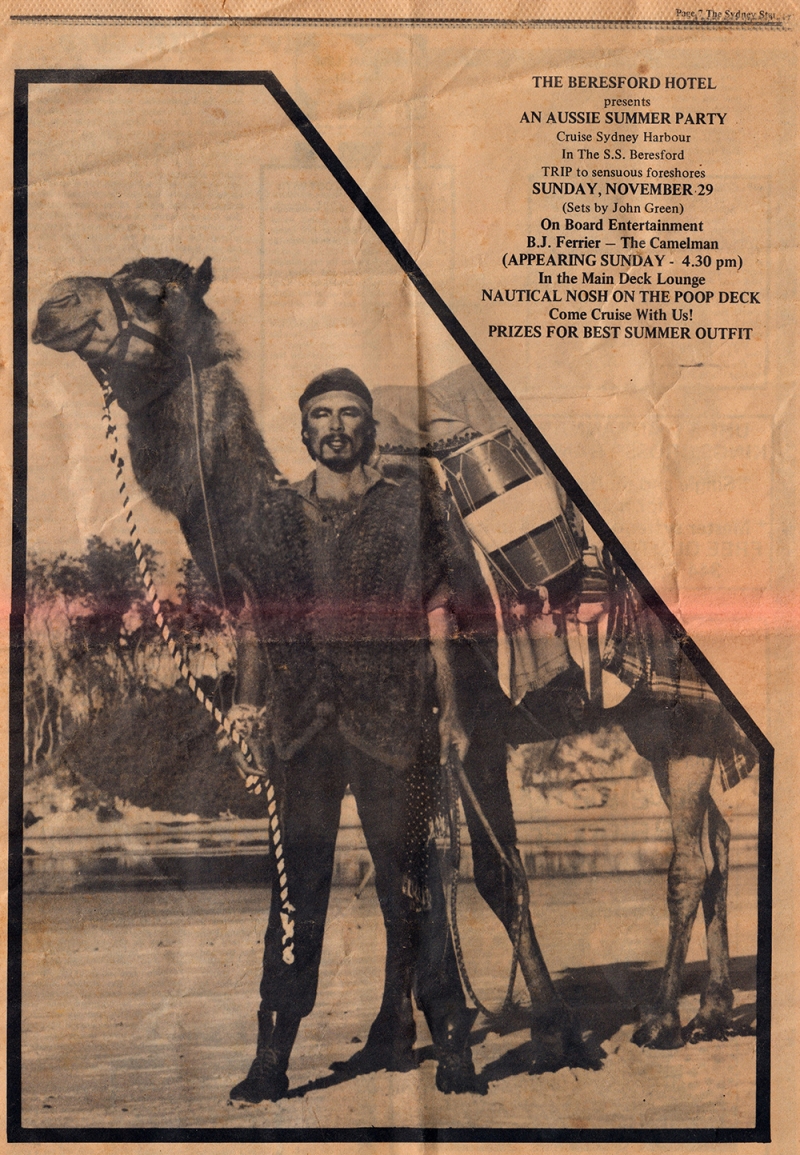

I once was the proud owner of four camels. The attached newspaper clipping is one of the only pictures of my camel adventures to have survived my house fire in 1994. The picture of me and Shanti my younger female Camel was taken in 1984 when I was paid by through an advertising agency to bring the camel team to Sydney for a publicity stunt to get promo for the opening of the Shell Building in North Sydney. A rather eccentric crew crossed Sydney Harbour in a barge with two large blue & gold cut-out palm tress, a half a tonne of white sand, the camels in splendid regalia, and my friend Rodney Gooch (a tribute to whom follows below) and I dressed as fugutives from the Arabian Nights (pre-terrorism and political correctness) and two belly dancers, the late Fairlie Beckner (a Australian middle weight karate champion)and Jennifer Carmen (a mystic and real belly dancer) and a third beautiful woman friend, Samantha Todd - under the harbour bridge (drinking champagne) and alighting near Luna Park. We were to walk the camels up through the centre of North Sydney where I was to play pseudo arabian disco music on borrowed synthesizers and a drum machine for the belly dancers. One of the camels nearly fell in the harbour when we were attempting to disembark. I actually did get on the Channel 9 news as, just after we landed, we were drenched by torrential rain! The "Ships of the Desert" byline was too funny for the news editor to ignore.

We appeared at the Shell building every day for a week. Shows were hosted by the glamorous Chelsea Brown, an African-American actress and comedian (who appeared as a regular performer in comedy series Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In with guest roles include appearances in Marcus Welby, M.D., Ironside, Matt Lincoln and, in the UK, The Two Ronnies. She also appeared in the films Sweet Charity, and The Thing with Two Heads. She emigrated to Australia in the 1970s and had ongoing roles in soap operas Number 96 (in 1977), and E Street (in 1990–1991). She had a guest role in the Australian-filmed revival of Mission: Impossible (1988). Film roles in Australia include Welcome to Woop Woop, The Return of Captain Invincible. She was married to fellow E Street actor, the late Vic Rooney. Wikipedia).

I first met the inimitable Rodney Gooch in the early eighties when I was performing a regular gig as a solo entertainer at a long-defunct restaurant called The Palms in the main street of Bangalow (a small town near Byron Bay on Australia's east coast - I have since made Bangalow my home).

Rodney had taken a job as a waiter and his powerful, flamboyant personality, huge hands and Rudolph Nureyev-like face made quite an impression. From conversations I only vaguely recall I have the idea that Rodney was a founding figure in the original Les Girls drag-show (of Kings Cross fame), had appeared on the cover of the international Face magazine, and run a restaurant in London, and ...crossed Australia, from Alice Springs to Byron Bay solo, with a team of camels and a dog.

Rodney and I, and a few others, were soon putting on hilarious high camp and rather gothic theatrical productions in this tiny performing space... most notably It's No Picture Show, starring myself, Rodney in drag, the wonderful singer/actress Glenda Lum, and journalist (now media advocacy lecturer) Gerald Frape (with whom I later wrote Goodnight World).

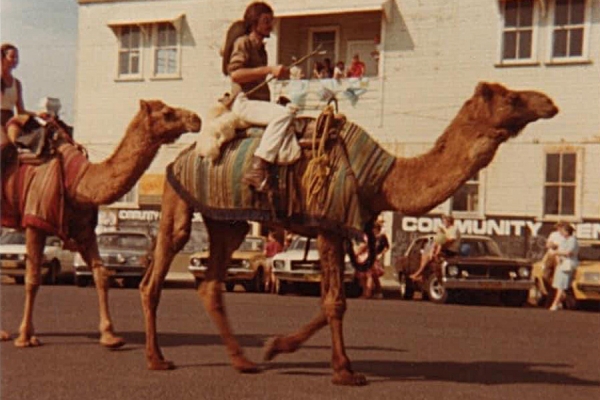

One of the pictures in the attached gallery is of me and my friend Robyn Bekker riding in the now historic Oleander Festival in Byron Bay. Back in 1981, I was invited to ride my camels up Jonson Street as part of the Festival Parade and here is an article from the Northern Star with a picture of myself mounted on Bunji the bull camel and Robyn Bekker riding Isabelle. Just after this photo was taken, the fire engine at the head of the parade let off it's siren... the camels took fright and bolted off the street and onto the footpath, galloping down the sidewalk. Have you ever seen a camel gallop? I had to crouch down and actually bumped my head on a shop awning as shocked onlookers scattered in all directions in pandemonium.

Who was the Gooch?

RODNEY GOOCH who in his life of unsung achievements was active and influential in the establishment of the first aboriginal recording studio, assisted the very earliest contemporary aboriginal bands to be recorded and recognised. After facilitating the start up of aboriginal contemporary music, RODNEY is credited with going on to influence the emergence of contemporary aboriginal painting, encouraging and enabling the many artists of Utopia community to pursue international careers in the arts. The late EMILY KAME KNGWARREYE was one of these artists, now regarded as one of Australia’s most significant artists of all time. Rodney also managed the CAAMA shop (the art, craft and music outlet of the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association) and Utopia Batik, of which he was art co-ordinator from 1987 to 1992.

Rodney was an original and a visionary. He had indeed made an epic, year long journey from Alice Springs to Byron Bay with four camels and a dog, crossing the Simpson Desert unassisted (an article was written on this trip by Gerald Frape for Hustler Magazine, long before the film Priscilla Queen of the Desert hit the silver screen, and in my mind Rodney was the true original Priscilla).

As I had purchased a small acreage, and Rodney was over his camel adventure I became the guardian of those foot-sore camels. In the coming months I began giving camel-rides at the local markets to subsidise my musical income and became quite a camel expert under Rodney's influence. You could meet the world on the back of a camel in those days. I rode them in local festivals and even began being booked for children's parties! These were only recently wild, feral camels but camel suffer from a maligned reputation .

The Gooch and I had many adventures, the most outrageous was that week-long publicity stunt for the opening of that brand new skyscraper in North Sydney - described above.

Rodney painted the two tall blue and gold cut-out ply-wood palm trees, and the climax was us crossing under Sydney Harbour Bridge on a sand-filled barge, with the four long-sufferring camels. Helicopter flying overhead, TV cameras whirring, our odd team high on champagne euphoria - but when we reached Luna Park, the tide was low and the camels wouldn't walk up a ramp. Rodney tried to urge our bull camel Bunji up the ramp and he took one disgusted step onto the plank and then nearly fell into the harbour - he lay there with his huge dromedary chest pressed to the barge deck, looking very disgruntled (even for a camel), with his two skinny front legs dangling over, perilously close to the murky harbour water.

After much confused disarray, we finally off-loaded onto a small patch of grey sand covered with city detritus clinging to the base of an old stone wall. We mounted on this strip of sand. Then it rained.

No, it poured (and thus amusing images of some rather soggy ships-of-the-desert made the Channel 9 News).

Rodney booked some music gigs for me around Sydney (the header image is an ad for one of those), and arrived on a camel and rode up the steps and into the hotel, dismounted on some sand on the dance floor he had wheel-barrowed in, and then played a rather strange set of pseduo arabian disco music - but the entry on camel back was a hard act to follow.

The following year Noel Fullerton's famous camel team was visiting the Gold Coast, and as Rodney knew Noel, he negotiated to put on a camel race in Lismore showgrounds. We borrowed money to finance and promote the event. There is a theme here - It rained again. The distressing outcome was that we had to sell our treasured camel team (they were dispersed to some large rural properties in western NSW to eat thistles) and the saddles to recoup the bank overdaft, so Rodney decided to return to Alice Springs to capture some more camels!

Some years passed and Rodney didn't return to Byron, and contact was disjointed. From what I heard later, Rodney began working as a chef to earn some money, but this was also the time when he began his life's work.

Rodney had always expressed a desire to make some sort of difference to the plight of Australia's indegenous people. Let's face it - Australia has a sad and sorry record and things have not improved greatly in terms of racism. Rodney first hired some local hall and put on a few indigenous rock bands - there was no venue in Alice Springs that would employ aboriginal bands. Rodney did the promotion, collected money on the door to pay the bands, and swept up the broken glass afterwards. These small entrepreneurial ventures were so successful that soon Rodney started working with the fledgling C.A.A.M.A. Radio group, based in a tiny cement block building in the squalid Gap aboriginal camp. During this period the seeds of the contemporary aboriginal music project described below were sown.

Rodney then began taking his choice of aboriginal bands to Adelaide to record them, releasing some home-grown cassette tapes, and continued putting on dances for aboriginal communities (who were largely uncatered for in Alice in those days), and even began making some wild, earthy video clips for bands such as the Warumpi Band. The cassettes had an incredible impact in the aboriginal communities - this was their own contemporary music and it had never been available before.

My next contact came when Rodney invited me to Alice to help develop appropriate practical legal contracts between the aboriginal bands and C.A.A.M.A., a project whcih severely annoyed some of the legal profession in Alice, and made me a target at some of the Alice society "do's" I attended - but their legaleze documents were incomprehensible to the parties involved. I collected specimen contracts from a broad range of recording and publishing companies in Sydney and Melbourne . I remember early mornings jogging in the green irrigated park in Alice, and physically cutting and pasting documents on the motel room floor (in pre-computer times) with the idea of editing down to the most concise but comprehensive documents I could manage. I finally "translated" this into a parallel explanation in everyday language, which Rodney then had re-translated into various aboriginal languages. He always encouraged a direct approach to problem solving.

The success of the music cassettes Rodney produced for C.A.A.M.A. - they went on selling like wild-fire on aboriginal communities across the N.T. - led to C.A.A.M.A. securing a grant to set up an aboriginal recording studio, which Rodney visualised as a mobile unit, travelling to the homelands of contemporary aboriginal music artists. I was employed to research the purchase of equipment for this project and later set it up for Rodney in a small bus he had purchased.

This was the first C.A.A.M.A. recording studio, and I was immediately sent to record an aboriginal concert in a park in Brisbane. The recording bus was a 'lemon' however. It was eventually abandoned. Rodney next flew me and the equipment, sans bus, to Broome. The equipment somehow ended up in Perth and I spent some time hanging about in pre-development Broome with my four year old son Tirryn. I was billetted in the aboriginal hostel - prossibly the first and only white man to stay there - and my beautiful boy was a blessing in bridge building. After much too-ing and fro-ing I was put in contact with an agent for the Chancellor of the Exchequer of Britain - forgotton his name now - who was buying up big in preparaton for the coming development boom... and it eventuated I was offered a deserted house on the beach out of town, where I set up the recording equipment. There was electricity and fans, and a working toilet, but no stove or furniture, and I cooked outside on a campfire looking down on my own little beach, no humans for miles, and the beach sand was red.

That summer I recorded Jimmy Chi's original demos of the songs which became Brand Nue Dae as well as the first recordings of Scrap Metal (now the Pigram Brothers ), and also secret traditional songs performed with solemn dignity by elders of the local community.

The weeks flew by and Christmas arrived. While I was home for a Christmas break, the lead singer of Scrap Metal died in a drink driving accident, my aboriginal trainee-engineer Eddie was arrested for apparently bashing someone to death with a star-picket in a drunken fight and meanwhile the precious master tapes we had recorded with such idealism and excitement were stolen by a white 'friend' of the band who thought they would be valuable. (They were eventually recovered, and years later I saw a copy of a finished cassette in an Alice Springs record store).

After the dust settled on this episode, the mobile 'recording studio' was finally set up in the concrete-block bunker at Little Sisters camp around the corner from the Gap, in Alice Springs, and the rest is history. Though a history these days that is on a downward trend - the exciting heyday of C.A.A.M.A. Recording a mute memory thanks to Howard Govt cuts to such expensive cultural icons.

So, in the whole early history of contemporary aboriginal music, that culminated in the establishment of the big glass-fronted C.A.A.M.A building in the centre of Alice Springs and the success of aboriginal bands, Rodney Gooch was a hugely important historical figure...it was his vision and energy which led to the establishment of a national contemporary aboriginal music presence in the media, a fact which goes largely unsung.

His later even more important work with aboriginal visual artists is much better recorded (see below). One could suspect it is because of his status as a gay H.I.V. victim that he is yet to receive the recognition he deserves, for a fabulous, inspiring life, and an immense contribution which paved the way for the acceptance that contemporary Australian aboriginal art and music now enjoys in mainstream culture, a cause to which he consciously dedicated himself over two decades. In time I hope his true historical significance will emerge.

Rodney touched many people. I remember him fondly as a flamboyant, larger-than-life, astute, energetic, totally unique individual, with an astounding constitution, able to withstand predigious feats of partying, a strong instinct for and love of visual style, music and culture, and a green thumb that turned the backyard of any place he stayed into an oasis.

But if history is just, we will surely remember him as a very practical visionary, and a life-long fighter for the cause he believed in and the Australian aboriginal people he loved.

Rodney Gooch: Devoted to bush art.

OBITUARY. from the Alice Springs News, Sept 18, 2002.

Rodney Gooch, who died recently, made a huge contribution to the artists, singers and musicians of Central Australia, say friends and family who contributed this obituary:-

Rodney was born in Adelaide in 1949, one of six siblings.

He left home at 17 and lived for a time in Sydney where he first performed as a drag queen, travelled overseas and lived on Norfolk Island before settling in Alice Springs. His first job here was on a camel farm, and his 4500km solo trek from Alice Springs to Byron Bay gave him the title of the original "Queen of the Desert". Rodney is best known for his work with Aboriginal artists and musicians. He originally joined CAAMA for a six-week period and began what became his life's work. He started by encouraging young people from the Gap Youth Centre to become involved in creating artwork for cassette covers for CAAMA Music, and he helped establish the CAAMA Shop.

His flamboyance, creativity and energy enthused many others to contribute to the Shop. It grew quickly under his management, providing employment for Aboriginal people and becoming a great drop-in centre and mixing pot for all, both black and white, to talk about art, music and new ideas.

In 1987, Rodney was asked to take over the management of the Utopia Women's Batik Group. The women took a shine to Rodney and he to them. Batik had been introduced at Utopia a few years earlier but it wasn't long before Rodney, through CAAMA Shop, was providing art materials to the whole community.

A trip to the United States in 1988 with Chris Hodges and the late C. Possum led to a survey of the Utopia artists to see if they would like to try acrylic painting, as US museums and galleries dismissed the batik work as "craft". This survey became known as "A Summer Project", the works later acquired by the Robert Holmes a Court Collection. Rodney provided the first canvases and paints to Utopia artists. He also encouraged people to paint on car doors, and provided wood carving materials, which led to the production of the now famous Utopia wood figures. His flamboyance and enthusiasm was infective and it showed in the freedom and colour that was displayed in the Utopia works. Artists such as Emily Kngwarre, Lindsay Bird, Ada Bird and Gloria Petyarre all commenced painting with Rodney's support.

EMILY KAME KNGWARREYE Anmatyerre (ca. 1916 — 1996)

NTANGE, MUNYAROO SEEDS DREAMING, 1996 synthetic polymer paint on canvas/linen

120 x 84cm $7,000 — 9,000 PROVENANCE Mulga Bore Artists (Rodney Gooch), Utopia, N.T. Company Collection, Melbourne EXHIBITED Switzerland: Gallerie ESF, Lausanne, July 1998; Gallerie Rivolta, Geneva, August 1998. Norway: Galleri Oda, Kristiansand; Galleri Lista Fyr, Borhag; Saviomuseet, Kirkenes; Alta Kunst-Forening, Alta, August to November 1999. In 1998 Rodney donated his personal art collection to a regional gallery in South Australia. His final collection was donated to the Flinders University Art Collection, a gift he organised while he was in hospital. Rodney was also important in the development of CAAMA Music. When CAAMA needed a place to record artists, but had no money, Rodney set about building a mud-brick recording studio at Little Sisters, with the help of many others. This became the place where many Aboriginal singers and bands laid down tracks for CAAMA Music.

The artwork, marketing and promotion was done under Rodney's management and it was a huge success.

Rodney loved and admired Freda Glynn and Philip Batty, who were running CAAMA during Rodney's time there, and between them they made a great contribution to the media culture of Central Australia. As Rodney's brother Bob Gooch said at his funeral, Rodney's life gives us "a message and example to think about. " Despite the recent decades being known as the era of greed, Rodney was the opposite. "He leaves us all with an example of a happy life, lived to the full, enjoying the simple things, the people, his family, the community."

"ART AND RECONCILIATION"

SPEECH BY EVELYN SCOTT CHAIRPERSON, COUNCIL FOR ABORIGINAL RECONCILIATION, AT THE OPENING OF "THE RODNEY GOOCH COLLECTION: WORKS OF THE ARTISTS OF UTOPIA" RIDDOCH ART GALLERY MT GAMBIER, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 25 SEPTEMBER 1998

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Malcolm Anderson, Mayor Don McDonald, Louise Haigh, Rodney Gooch, Ladies and Gentlemen.

"First I'd like to thank Malcolm for his welcome to the country of the Nungis people. In keeping with a tradition of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, I acknowledge the living culture of the Nungis people and the unique role they play in the life of the Mount Gambier region. The reason for us being here tonight is more than just a proud moment for the Riddoch Art Gallery and the people of the South-East region. It's also a significant milestone on the path to reconciliation between Indigenous peoples and the wider Australian community.

I'll explain why I say that in a minute, but first I'd like to pay tribute to some of the people who've made it possible for Mount Gambier to become home to this wonderful collection of art. Most of you have probably heard of the gallery's generous benefactor on this occasion, Rodney Gooch. Rodney is widely and rightly hailed for his pioneering work in developing and promoting Indigenous arts in Central Australia. We know that he has cast his net widely in that field over the last couple of decades.

For example, he was one of the driving forces behind CAAMA - the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association. CAAMA has played a leading role in promoting cross-cultural understanding, in providing a voice for many Aboriginal communities, and in supporting the several important Indigenous languages that remain alive in the vast area through which its coverage extends. And CAAMA became a model for what is now a quite impressive network of Indigenous media operations throughout Australia.

Rodney Gooch's part in all of that was important and, especially in the early days, courageous. But of course, it's one of his other great pursuits that interest us most here. That is his long-standing and energetic encouragement of Aboriginal artists and, hand in hand with that, his determination to help all Australians to an appreciation of the meaning, the significance, and the artistic merit of Indigenous art.

In the course of this labour of love, Rodney built up a significant private collection of the work of the artists of Utopia. It's entirely consistent with his vision that all these exciting and valuable paintings, sculptures, coolamons and other works are now becoming available to the Australian public. I think I can speak on behalf of all Australians interested in cultural diversity and mutual understanding when I pay tribute to the generosity, and the vision, of Rodney Gooch.

The question then is, why Mount Gambier? Why the Riddoch Gallery? This is after all one of the most significant gifts to a regional gallery ever made in Australia! I think the answer to that lies in the energy and commitment of your director, Louise Haigh, and the many supporters of the Gallery in Mount Gambier and the surrounding region.

I believe Rodney decided quite some time ago that his collection would become available to the Australian public, but he was quite fussy about how it should be cared for and used, especially for the benefit of Australia's children. I know that Riddoch, like most regional galleries, is hardly flush with funds, so it's a feather in Louise Haigh's hat that she was able to meet Rodney's requirements and take on the responsibility for this fine collection. I know that Louise knows she couldn't have done it without specific support for the collection from a number of quarters. The City of Mount Gambier, agencies of the State Government, and Living Health all deserve praise for their ability to see the worth of the collection and ensure it found a home here. I heard also that a couple of months ago, the preparation of this exhibition received a big boost when the local business community and some hundreds of citizens of the region made sure that a fundraising auction was both thoroughly enjoyable and successful in its purpose.

It's this last source of support that leads me back to the comment I made about the importance of this occasion to the national process of Reconciliation. The Council I lead will end its life on the first of January, 2001. By then, I believe we will have taken many steps together on the path to reconciliation between Indigenous peoples and other Australians.

The Council itself hopes to achieve by that time broad agreement on national documents of reconciliation. These will set out the nation's understanding of the unique place of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the original inhabitants of this land, acknowledge past injustices, and lay down the steps that still need to be taken to overcome Indigenous disadvantage and achieve true and lasting reconciliation.

We also hope to see in place a great network of partnerships, between business, government of all tiers, community organisations and Indigenous communities, established with the prime objective of ridding this land of the gross inequalities that still persist in relation to our Indigenous peoples. There's a third, and I think vitally important, goal for this third and last term of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation. It is to support and promote the growth of the People's Movement for Reconciliation. This is the key to maintaining the momentum for true reconciliation beyond the centenary of federation. Less than two years ago, there were about twenty local groups in all of Australia working under the banner of Australians for Reconciliation. Today, there are more than 260, and we want to see that number grow much more. It's at the local level, where people of good will can sit down together and agree on what reconciliation actually means in their communities; where Indigenous and other Australians can learn to appreciate each other's outlooks on life, where they can see what needs to be done and plan to do it, that reconciliation has the greatest meaning. I believe that this people's movement has an unstoppable power. Whatever the political threats that may emerge from time to time, the people will ensure that reconciliation succeeds.

It's in that context that I so very warmly welcome the kind of partnerships that led to this great event in Mount Gambier. Your City Council, your business community, your Indigenous community, your private citizens of good will, all came together to make sure this project worked. The fact that this project is a major demonstration of Indigenous culture makes it - and the way it's been brought to fruition - is a highly significant milestone in the path to reconciliation. So it gives me great pleasure and pride, ladies and gentlemen, to declare the Rodney Gooch Collection of the Riddoch Art Gallery, officially open." The Rodney Gooch Collection - the Riddoch Art Gallery The Rodney Gooch Collection of indigenous art from Utopia was a donation of over 200 works of art from Rodney Gooch in 1998. Gooch was a long-time supporter of the aboriginal music and art industries in Central Australia and worked with aboriginal people and organisations for over 20 years. Since 1987 Gooch forged a close relationship with the people of Utopia, which is 240kms north east of Alice Springs, and in the summer of 1988/89 he delivered 100 fresh canvases, acrylic paints and brushes to various artists in Utopia. As a result of this many outstanding indigenous artists began to emerge including Kathleen Petyarre and the late Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Through the generosity of Rodney Gooch, the Riddoch Art Gallery now owns a significant collection of works from Utopia including silk and cotton batiks, sculpture, jewellery, photography and a large number of acrylic paintings. This collection spans two decades and traces the development of the artists of Utopia from relative obscurity to international recognition. Johnny Skiner, Bush Plum Dreaming, c.1992, acrylic on canvas, 165.5 x 44.5 cm. Gift of Rodney Gooch 1998 Collection - Riddoch Art Gallery, Mount Gambier. Janet Kngwarreye, Untitled (Utopia massacre scene), c.1998, acrylic on canvas, Gift of Rodney Gooch, 1998 Collection - Riddoch Art Gallery, Mount Gambier. Over the past decade Aboriginal artists have produced distinguished works because of their individual style and techniques rather than just for their ethnographic importance. Names such as Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Robert Cole and Ronnie Tjampitjinpa have become well know within Australia's art community because of their work's distinctive and exceptional qualities.

In a foreword in one of several books on the Utopia art community (artists from the Aboriginal Utopia community in central Australia in the Northern Territory), The Art of Utopia by Michael Boulter, Hodges said: "Looking back over the work that they made since the late 1970s, and in particular the work since 1988, it is clear to me that the most outstanding work goes beyond Aboriginality." He added: "The art transcends specific cultural roots and references and thus becomes meaningful to a much wider audience."

Hodges first encountered Utopia artists' work in the contemporary Australian section of the Australian National Gallery. Then he met Rodney Gooch by "accident", (when Gooch was working as) a representative for the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA), in 1988. Gooch had organised Utopia women's batik group to produce a series of stories as a way to document the culture of their region. This process involved using brushes to apply hot wax artistically on material, such as silk, which was then dyed. Because of the size of pieces such as A Picture Story (2.4m x 1.2m) Gooch needed spaces the size of galleries to exhibit the work. Previously they had been shown in the CAAMA shop, a converted generator shed. Gooch's meeting with Hodges ended his problem of finding a space.

They agreed Hodges would exhibit and sell work for the Utopia community in Sydney. Initially the work was shown in his Newtown studio/home. The positive response from this and several temporary exhibitions led him to open a permanent gallery in Stanmore. Soon after the Papunya Tula Artists approached Hodges to be their representative. Consequently, Hodges became a gallery owner "more or less in a response to what they asked me to do for them". So he decided to create the same type of environment he had found productive as an artist starting out. Hodges said: "I believe strongly in the idea of the artist and the gallery working together in representation."

EMILY KNGWARREYE (Australian Representative to the 1997 Venice Bienalle). Emily is widely regarded as the most innovative painter to have emerged from the desert painting movement. The evolution of her painting style was nothing short of remarkable. Emily started painting at Utopia at the age of 77 and compressed a brilliant career, comparable to that of other important abstract painters, into eight short years, leaving an impressive body of work behind her. Emily passed away in 1996, but her legacy lives on in the compelling colour, vibrant dotting, and spellbinding gestural brushwork of her paintings.

Emu Country

Emily Kngwarreye,

1993 60" x 36"

A mid-period gem, its soft colours evoking a sense of desert landscape in bloom, as the Emu hunts for the Mulga seeds heralding the seasonal renewal of the Yams (Emily was the senior custodian of the Yam Dreaming).

Barry Ferrier

Barry Ferrier (aka Barry Ferrier) is a Byron Bay based Australian musician, songwriter /composer and multimedia designer.